Steve Sanderson

Taste vs the Algorithm: What Oi Polloi’s Steve Sanderson Did Next

From Oi Polloi to Karévan, and from shopfloor to algorithm — a case for taste in an optimised world

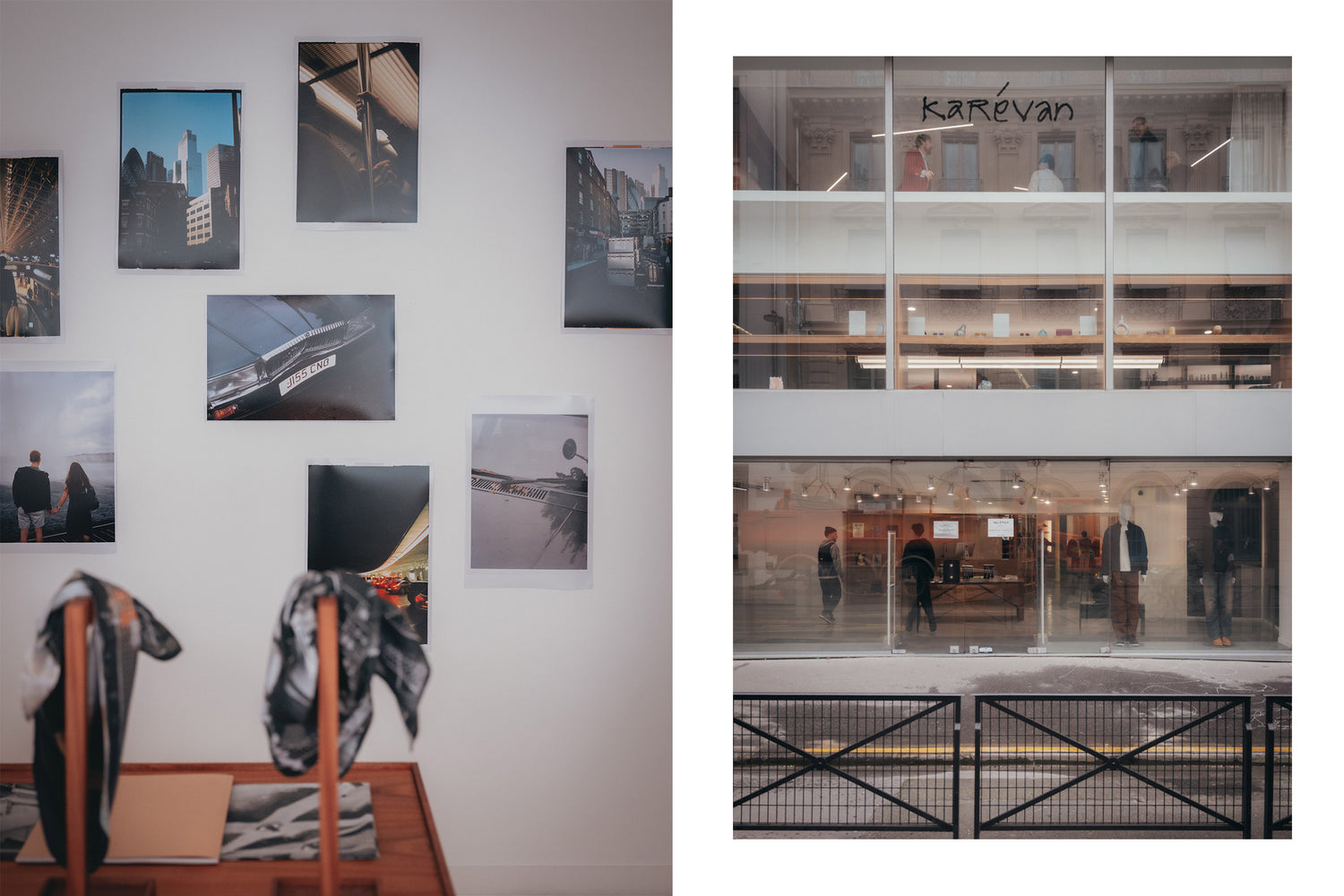

This week, MARRKT landed in Paris Fashion Week to help our friends Steve Sanderson and Graeme Fidler launch their new concept Karévan at The Next Door showroom. It was great to see friends old and new, and fashion writer Alfred Tong sat down with Steve to discover why Karévan is bringing the human touch back to retail, collaborations and design.

Last week I got a call from Karévan co-founder Graeme Fidler, whose design CV includes a stint at Ralph Lauren in New York and a spell as design director at Aquascutum. At first, I assumed he was calling to ask whether I was heading to Pitti Uomo. Instead, he wanted to tell me about a venture he and Steve Sanderson, co-founder of Oi Polloi, had been quietly working on.

On first impression, it sounded odd: a shop that does everything a shop does except sell things. And then I realised that was its quiet genius.

Retail, done the Oi Polloi way — tightly edited, with a point of view — once acted like a form of publishing. Shopkeepers bought strange, unfamiliar things and explained why they mattered. “We’d go around finding things people had never heard of and put them into a different context,” Sanderson says.

“Why don’t we just do the part we’re actually good at — ideas, product, collaboration?"

So what is Karévan? First, there’s actual gear: exclusive iterations of products from companies they admire, developed either as collaborations or as sub-brands launched under the Karévan umbrella. Early projects include work with British shoemaker Sanders, Italian luggage maker FPM Milano, cult Japanese label Mini-Tet, and MARRKT.

At launch, this includes Double Cashmere, a line created with Scottish knitwear manufacturer Lyle & Scott. Think of it less as a one-off collaboration and more as a brand within a brand — closer to RRL at Ralph Lauren — with its own identity and point of view, while still sitting inside the parent company’s world.

In practice, Karévan operates as a design studio, a showroom and a publishing platform rather than a retailer in the traditional sense. It develops products with manufacturers it admires as parallel identities, and supports this with a Paris showroom, alongside printed fanzines, online output and irregular releases that recall the magic once exercised by mail-order catalogues.

“Catalogues were how you learned taste,” Sanderson says. “They weren’t just about selling things — they showed you how clothes fitted into a life.” He points in particular to the big-budget J.Crew catalogues of the past — people in canoes, scaling mountains, riding horses, fishing, laughing. A life lived right.

The common thread is simple: the creation of a world and a point of view that other people want to immerse themselves in.

To understand why Karévan exists, it helps to look back.

The great British shopkeeper deserves to be held in the same regard as Vivienne Westwood, Central Saint Martins or The Face — an unsung but decisive force in shaping taste and influencing how the nation dressed. Style is made on the shopfloor and in the dressing room, with the results played out in public: on football terraces, in nightclubs, and on the street.

One such institution was Oi Polloi. Founded in Manchester in the early 2000s by Steve Sanderson and Nigel Lawson, it took this local, instinctive model and scaled it through the early internet — helping to transform such unlikely items as Birkenstock sandals and Berghaus anoraks into global fashion.

From one man finding an unusual jacket in a warehouse in Germany and saying, “hang on a minute, this is cool,” to a punt on the shopfloor in Manchester’s Northern Quarter, to being worn onstage by Liam Gallagher — this is the real story of how grassroots style is made.

I first met Sanderson in 2015, when Oi Polloi — still riding high — opened an outpost on Marshall Street in Soho. He was wearing a jacket by Sassafras, the Japanese label founded by Takashi Takagi, originally designed for gardening, with pockets placed exactly where you might tuck the stems of roses. Japanese gardening gear — for my walks on Hampstead Heath. I was immediately hooked.

Unlikely, strange things you’d never heard of — sold in central London, next to Patagonia or Stone Island. This was what made shopping sexy and fun.

Then came JD Sports — and the algorithms.

“We were promised one thing, and then something else happened,” says Sanderson. “They took on a lot of independent stores and just weren’t in a position to operate them — it didn’t fit together.”

The same tools that once carried Oi Polloi’s taste beyond Manchester — e-commerce, SEO, online publishing — now worked against the instincts that had built it.

“We’d get people into something, put it into a different context and make it relevant,” Sanderson says. “And then someone else would pick it up and sell far more of it.”

The mechanics of that shift were unforgiving. “We’d go into a showroom with hundreds of SKUs and come out with maybe twelve — that editing was the point,” he says. “But once someone else carries seventy, they’re suddenly more relevant than you in search.”

“We were making more money when we were smaller,” he adds. “The bigger we got, the worse the business became.”

Oi Polloi was acquired by JD Sports in 2021; by March 2023 its Manchester Northern Quarter shop had closed, marking the end of an era for the independent shop as tastemaker. “That whole thing probably affected me more deeply than I realised at the time,” says Sanderson. “It hit me later.”

Fidler, who has also experienced the brutal churn of the fashion business — his own brand, Several, closed in 2016 — is philosophical about the cycle. “One thing about this business is it keeps changing,” he says. “I’m still learning so much, even after all this time.”

Karévan takes the parts of retail that once mattered — judgement, curiosity, editing, context — and separates them from the mechanisms that ultimately hollowed them out. In an era where taste is routinely discovered by algorithms and monetised elsewhere, it proposes something quieter and more radical: that value still begins with a human point of view.

“There’s an incredible amount of information out there now, and a lot of it is bad,” Sanderson says. “People are being told what to like by people who don’t really have any depth of knowledge.”

Not a shop in the old sense, but the continuation of the shopkeeper’s role by other means.

Pieces from Steve's personal archive are available to shop below.

Photography by Dan Watson. Words by Alfred Tong.